A practical guide, we’re not going deep here

Background and history

Docker is an Open Source Software project started in 2013 that largely popularized the idea of “containers” by making them easy to use and implement through a command line tool and a “Dockerfile”, which is essentially a file that defines your container’s environment.

But the concept of a “container” has been around since 2008. A “container” is just a process that has specific control groups and namespaces that limit their access to resources. This combination of control groups and namespaces effectively gets you close to process isolation.

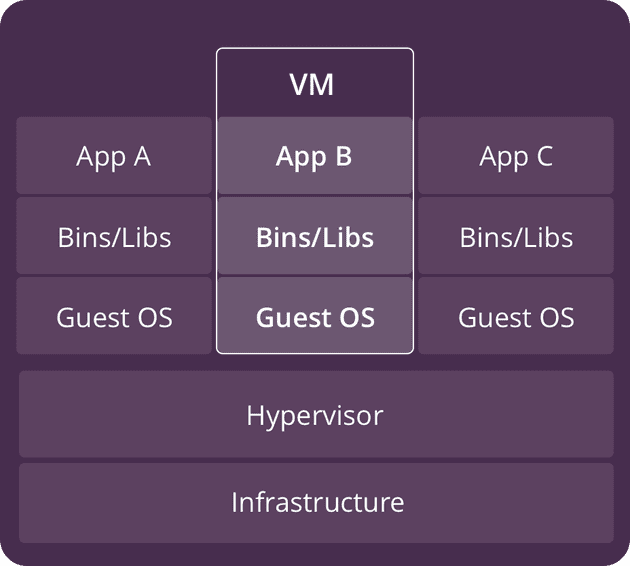

Your next logical question is: process isolation -> Virtual Machine(VM)? Yes! And no. VMs are the extreme here: they guarantee full process isolation but at a large cost to CPU and memory. In real applications, while full process isolation is ideal, it’s by no means necessary, so VMs have a lot of overhead for not a lot of gain.

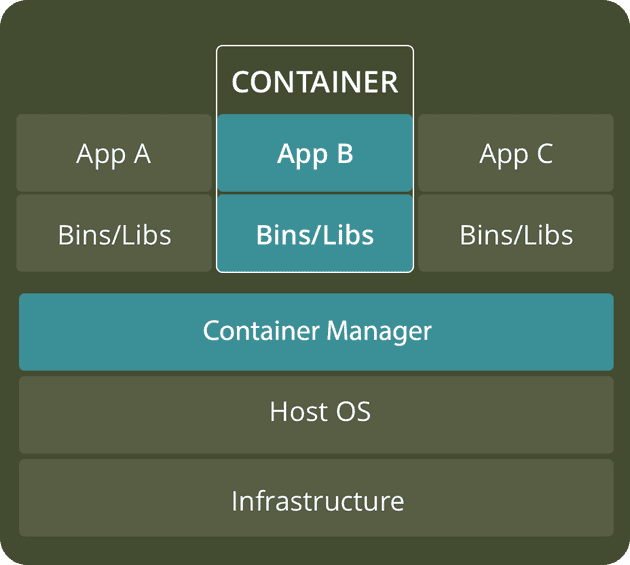

The images below are from this (great) article by BlackBlaze: What’s the Diff: VMs vs Containers comparing the two solutions more in depth.

|

|

|---|

So let’s use containers

Since containers make use of the host’s operating system (OS), they can be much, much lighter than VMs (The alpine image from Dockerhub is just 5MB while typical VMs deployed on tintree ranged from 20GiB to 160GiB in size).

Enter Docker

Like I said before, Docker mostly just popularized Linux containers by making them easy to use. So let’s see just how easy it is to use them.

First, you’re going to need Docker installed and the command line interface (CLI) available on your system’s PATH. See installing.

Let’s start with the most basic “Hello, world!” Python app:

Open up a terminal and create a new directory learnyouadocker, cd into that directory and create a main.py file with the following contents:

print("Hello, world!")Great, now we need to containerize this. In Docker-land, this means:

- Creating a Docker image

- Running the container

“What’s a Docker “image”? I thought this was about containers?”

Think of images and containers in the same way you do classes and objects in Object Oriented Programming (OOP). A class defines the properties and methods, while an object is an instance of a class. Here, an image defines the environment (dependencies, source code, environment variables, etc.) and a container is an instance of an image. In OOP, you have one class but can have infinitely many objects of said class; likewise, in Docker, you have one image but can have infinitely many containers of said image.

Dockerfile

A Dockerfile is your class file from the analogy above. This is the file you use to declare your environment, dependencies, source code etc.

Create a file called Dockerfile in the same directory as main.py above and add the following:

FROM ubuntu:18.04

WORKDIR app

RUN apt-get -y update && apt-get install -y python3

COPY main.py .

CMD ["python3", "main.py"]And now let’s walk through it, line by line.

FROM ubuntu:18.04 This “bases” your Docker image on Ubuntu 18.04, meaning subsequent statements in the Dockerfile will behave as if you are issuing commands on an Ubuntu machine. When you are creating a Docker image, you create it based on a pre-existing image, and you can find thousands of them on docker hub. Dockerhub is what’s called a container registry and is the default registry where Docker will look when parsing a FROM statement in a Dockerfile. If your base image lives in another registry, for example, AWS’s Elastic Container Registry, your FROM statement will need to be more specific : FROM aws_account_id.dkr.ecr.region.amazonaws.com/my-base-image.

If your Dockerfile only had FROM ubuntu:18.04, you could then run docker build -t my-ubuntu . to build, then docker run -it my-ubuntu and see the following (don’t worry, I’ll come back to what these commands mean later):

root@804343adee02:/# ls

bin dev home lib64 mnt proc run srv tmp var

boot etc lib media opt root sbin sys usrCongrats! You are now running an Ubuntu container. But let’s keep going.

WORKDIR app As you can see above, having just a FROM statement gets you a filesystem to work with, and it places you in the / directory. We could continue without this step and copy our source code over into the image COPY main.py ., but that would place our main.py file right in the root directory. While I’m sure you can think of a few reasons why this is a bad idea (such as the same linux user that runs your application also owns the root filesystem), consider how messy this gets as soon as your project evolves beyond a 1-file 1-line “Hello world” app. To preserve your sanity and for many security reasons, we create a “working directory”, or WORKDIR, where all subsequent steps in the dockerfile will be processed. Doing this is analogous to running the command mkdir app && cd app. In another tutorial I’ll talk about how to address the security concern of running your app as the root user, which is the default in docker.

RUN apt-get -y update && apt-get install -y python3 This is a Python application! We need a Python interpreter, and this is one way to install one.

COPY main.py . This command does exactly what it says: it copies main.py from my filesystem (aka where this Dockerfile lives on my machine) into the current directory of this image (ok, maybe not exactly what it says). The official docker documentation for COPY says: COPY <src> <dest>, but it’s more like COPY <src on my machine> <destination in image>. That may seem obvious to you, but it helps me to think of it this way.

Cool! Now we have an Ubuntu image with Python3 installed and our main.py file copied over.

The last thing to do is to tell Docker how to “run” a container of our image. That is, define a run command: CMD

CMD ["python3", "main.py"] This tells Docker to run python3 main.py when it comes time to start a container of this image. There are a few ways to write the CMD statement, and I have to look it up everytime: CMD. The only one that’s intuitive is the last one, but the first one is what’s recommended for reasons TM, so that’s what we use.

Putting this all together, we have the Dockerfile above (I’m repeating this because I hate when an article makes you scroll all the way to the top and then back down and then up again because you forgot something and then back down again)

FROM ubuntu:18.04

WORKDIR app

RUN apt-get -y update && apt-get install -y python3

COPY main.py .

CMD ["python3", "main.py"]Building your image

Great, now let’s build this thing and run it. Remember those commands I said I’d get back to before? Here we are: docker build:

docker build is how we (you guessed it!) build our image from a Dockerfile.

docker build --help shows the following (cut very short for the purposes of this tutorial – if you want the full output run the help command yourself):

~/dev/shane

❯ docker build --help

Usage: docker build [OPTIONS] PATH | URL | -

Build an image from a Dockerfile

Options:

-f, --file string Name of the Dockerfile (Default is 'PATH/Dockerfile')

-t, --tag list Name and optionally a tag in the 'name:tag' formatThe command we used earlier to build our Ubuntu container was docker build -t my-ubuntu . Dissecting this, we have docker build -t my-ubuntu and . corresponding to the help “Usage” line docker build [OPTIONS] PATH | URL | - where -t my-ubuntu is our option(s), and . is our PATH (ignore URL | - for now, unless you can’t, in which case, go to the docs).

-t my-ubuntu This is simply tagging out build so that we can easily reference it later when we do docker run, but it’s also for when you go to push your image to a registry (something you’ll most likely have to do if you intend to run your containerized app on some server)

. This is our path and is telling the Docker engine where to start building from. Remember COPY main.py .? This works here because main.py is in ., but let’s say you wanted to keep your main.py in a src folder like so:

~/dev/shane/docker

(docker2) ❯ ls

Dockerfile src

~/dev/shane/docker

(docker2) ❯ ls src

main.pyThen, in order for docker build to work with the Dockerfile that we’ve written here today, you would need to call the build command as docker build -t my-tag -f Dockerfile src. The -f Dockerfile here becomes necessary here because Docker assumes that your Dockerfile is in the same directory as the PATH argument to the docker command. The -f argument can also be nice if you want to store your Dockerfiles somewhere else in your project directory.

Okay, time to actually build docker build -t my-app . You should see the statements FROM RUN COPY happen in order and eventually see a confirmation along the lines of

=> => writing image sha256:2217efb567c567984065d9ffca956eeb4f27db6032e96628c6ede9fc72692010 0.0s

=> => naming to docker.io/library/my-appIf you want to confirm that this worked, you can run docker images | head and you should see

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

my-app latest 2217efb567c5 2 minutes ago 134MB

...Running your container

Finally, time to run. docker run my-app

docker run --help shows the following (cut very short for the purposes of this tutorial, if you want the full output, run the help command yourself):

~/dev/shane

❯ docker run --help

Usage: docker run [OPTIONS] IMAGE [COMMAND] [ARG...]

Run a command in a new containerBreaking our command down, we have docker run my-app as docker run [OPTIONS] IMAGE where my-app is our image (you can also use the IMAGE ID that you see when you run docker images, but it’s nice to use real names when you have multiple containers running)

Running docker run my-app should give us the following:

~/dev/shane/docker

(docker2) ❯ docker run my-app

Hello, world!A nice tool to have in your belt here is to be able to go inside this container in case you need to debug. From the “Usage” instruction in the docker run --help command you can see that we can pass a COMMAND, and doing so will actually run that command instead of the one we defined in our Dockerfile using CMD. To open a bash in your container, try docker run -it my-app bash and you should find yourself inside the container, inside /app (defined in the Dockerfile).

The -it in that command stands for “interactive” (i) because we want to be able to type commands in our bash shell, and TTY (t) which attaches the input/output streams of the container to our terminal.

And we’re done. You now know how to go from 0–running apps using Docker. Watch this blog for future posts:

- Tips and tricks

- Interacting with the outside world (AKA how to containerize a web server)

- Advanced topics: memory and CPU management

- Docker compose: running multi-container applications

- Compose-file project templates (Django, Rails, MERN, Airflow)