You’re not a dummy. The language used in git is old and unique to git: commit, staged, rebase, bisect, reflog, push, pull? Archaic. But it’s the industry standard version control tool, and one that you’re going to use every day, so it’s probably best to learn it. In this post we will walk through basic concepts and an easy workflow that you can adopt

What is git?

Git is a version control system. If you’ve ever written a paper for school and by the end of the assignment you have “MyPaper-draft.docx”, “MyPaper-revised.docx” and “MyPaper-final.docx”, then the idea of git should be a little familiar. The difference is that with git you don’t save entire new versions of your paper (or code), you just save the changes you make from the last “save”.

Each “save” to git is called a commit. A commit represents the changes you’ve made in your project relative to the last commit. A commit has a hash or ID that will be unique accross your entire project (i.e even if you have 100,000 commits, they are all guaranteed to be unique), and a message so that another human can look at a commit and understand what the purpose of this commit was.

A crude example

> ~/code

> mkdir git-intro && cd git-intro

> git init

Initialized empty Git repository in /Users/me/code/git-intro/.git/(Take note of the directory created in our project .git, we’ll be coming back to this in a different post but if you want to check it out you can take a look around ls -a && cd .git/)

Like the message says, we’ve just started a git repository with no history. Let’s go ahead and create our first commit:

touch main.pyThis creates an empty file, and even though the file is empty, it represents a change in our project and so we should be able to “save” this point in our projects history with a commit. But let’s check!

git statusThis is my most used command, I am constantly checking what the status of my git repo.

git-intro git/main

❯ touch main.py

git-intro git/main

❯ git status

On branch main

No commits yet

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

main.py

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)The status command is good for seeing the three possible states of a file in your project:

- Which files aren’t being tracked yet (new files, like we have now!)

- Which files have been modified, but not ready to be commited

- Which files have been modified, and are ready to be commited (this is called being staged)

What we want to do is add “main.py” to our git history and we do that with git add

git-intro git/main

❯ git add main.py

git-intro git/main

❯ git status

On branch main

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: main.pyAgain, run git status to see what the state of our project is and you’ll notice it’s changed. When we run git add main.py we are adding main.py to the “staging” area of git. The staging area is reserved for files (or changes) that are ready to be commited to git history.

The next thing to do is to commit this change to history

git-intro git/main

❯ git commit

[main (root-commit) 6b7a1fb] First commit

1 file changed, 0 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

create mode 100644 main.py

git-intro git/main 9s

❯ git status

On branch main

nothing to commit, working tree cleanWhat my terminal output doesn’t show is that when you run git commit, this will open the “vi” editor. The editor is a bit special and has “modes”. For now let’s just focus on getting this commit message done; when vi opens a file you start in “normal” mode (notice that typing characters doesn’t actually insert any text?), but we need to get to “insert” mode. While in normal mode, press “i” to enter insert mode and you will be able to insert text as you expect with a normal editor. Write a message that describes what you’re trying to save to your history; for something as simple and purposeless as this, “Initial commit” will suffice. Once you’ve entered your message, press “ESC” to re-enter normal mode. From here type “:wq” or “:x” to save and exit and you should see the terminal output above. And of course we run git status again to see where we are.

Let’s modify main.py to print out “Hello world”, save and check this in to git.

git-intro git/main*

❯ git status

On branch main

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: main.py

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")Since main.py already exists in history and we’ve just modified it, it shows up as “modified” when we run git status. If you want to see the modifications, you can run git diff and this will show all of the changes to every file that has been modified. It won’t show the changes that are staged, however, so if you want to see those changes you can pass the staed flag git diff --staged

git-intro git/main*

❯ git add main.py

git-intro git/main*

❯ git status

On branch main

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

modified: main.py

git-intro git/main*

❯ git commit -m "Hello world"

[main da8511f] Hello world

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)The “-m” flag passed to the commit command stands for message and is a quick way to bypass needing to deal with vi like I showed above.

So how do you know that you’re maintaining history and how can you see the history? git log

git-intro git/main

❯ git log

commit da8511f4b78f0b25b27e336a15538ac5c5ff481b (HEAD -> main)

Date: Mon Mar 29 09:47:38 2021 -0400

Hello world

commit 6b7a1fba279d8a1954223e086f9f04f511aef1e9

Date: Mon Mar 29 08:58:22 2021 -0400

First commitWant to see what happened in a specific commit? git show <commit_id>

Try showing the last commit: copy the commit id found when you run git log and then run the show command above. See that it’s just showing you what’s changed in main.py?

Forgot to add some changes to your last commit? No sweat, “git add” those changes and run git commit --amend. This will open up the “vi” editor pre-populated with your last commit message. Since you’re just adding files that you forgot when commiting last time you can go ahead and run “:x” to save and exit.

Remotes: where our code actually lives

You’ve probably noticed that I’ve rambled on about git without even mentioning git(hub | lab | etc) yet, which means all of our changes and histories have been local; but in reality your teams code lives on the cloud somehwere because it’s not just you working on this code, it’s a whole team and everyone needs access! This is where git remotes come in to play.

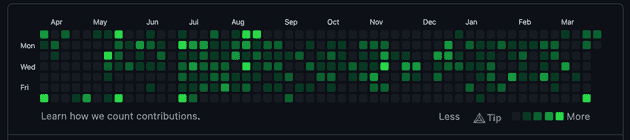

If you run git remote -v in our project you get an empty output. This is a problem because the reason we write to code is for the github commit tracker, right? Right.

So let’s upload this code to github! In the git world we call this pushing, we push code when it’s ready. Go to github (or whatever git client you like, gitlab, gittea, bitbucket etc. I’ll be using github for this post) and figure out how to create an empty repository.

Once created it should show you your git url, something like https://github.com/me/git-intro.git … this is going to be the url where our code lives.

In the project directory, run git remote add origin <url> and then git remote -v

git-intro git/main

❯ git remote add origin https://github.com/me/git-intro.git

git-intro git/main

❯ git remote -v

origin https://github.com/me/git-intro.git (fetch)

origin https://github.com/me/git-intro.git (push)What we did here is called adding a remote, which is what git uses to push and pull code to/from (we’ll come back to pull, let’s focus on getting our code out there). It is typical for the main place that you’re going to push code to to be called the “origin”, but you can name this anything you want and you can have many remotes! (This is actually how you deploy with heroku, you have your origin remote where your team can see your code, manage pull-requests etc. and you have a heroku remote so that when it’s time to deploy you can run “git push heroku master” and that will upload your code to heroku servers)

To upload the code we wrote, or push it, we can now run git push origin and when we revisit our repository in github we should see our main.py file and 2(!) commits. It’s imporant that you realize that github is keeping all of your commits, it’s not just a file server like dropbox or google drive.

Fetching and pulling

Running git remote -v shows you where github will be pushing code from, but also where to fetch it from. When you work on a team other members will be contributing code and the “main” branch will be updated. Suppose someone commits and pushes changes that you need in order to add a new feature? You need that code on your local machine, you want your machine to be in sync with what’s on github. This is where git pull comes in; pulling is doing two things

- Retrieving or fetching the changes on your remote

- Applying those changes on your machine

If you were to run git pull right now you would see a message like “Branch up to date”. This is because the latest change on github is also the latest change on your machine, but when you work on a team and someone else commits to the “main” branch, you will be able to run “git pull” and see new commits added to your machine (check it out with git log).

Branching: or how teams work in parallel!

You’ve probably noticed that in all of my shell commands so far you see “git/main” or on yours maybe “git/master”. When you initialize a git repository it creates a history with a “master” copy of your project and this will be the “main” copy that all future work derives from.

In a team you are going to have multiple engineers all working on the same project, modifying the same files all trying to get their changes into the main branch that will eventually get deployed to production so that users can start using those changes. But we can’t all be commiting directly to the main branch at once (to be honest, we could but that’s for a different post). Not only that but your team probably using a feature branch and Pull Request (PR) workflow. Let’s look at an example with the project we’ve been using this entire post.

Let’s say we get a feature request that we need to be able to double a number that a user supplies on the command line as an argument. The first thing to do is to create your feature branch; this is where you will develop code specifically for this feature.

To see all branches on in your project and which branch you’re currently on you can run git branch, to create a branch supply a branch name git branch mybranch and to switch to your branch git checkout mybranch

git-intro git/main*

❯ git branch

* main

git-intro git/main*

❯ git branch feat/double

git-intro git/main*

❯ git branch

feat/double

* main

git-intro git/main*

❯ git checkout feat/double

M main.py

Switched to branch 'feat/double'

git-intro git/feat/double*

❯ git branch

* feat/double

mainA quicker way to create and branch and switch to it is

git checkout -b mybranch

Now let’s build out our feature by defining our main function and the double function, then adding some command line argument handling

# main.py

import sys

def double(x):

return x * 2

if __name__ == "__main__":

print("Hello world")

num = float(sys.argv[1])

print(f'Double {num} is {double(num)}')And let’s write tests for that double function!

# test_main.py

from unittest import TestCase

from main import double

class MainTests(TestCase):

def test_double(self):

# Prepare

num = 4

# Act

result = double(num)

# Assert

expected = 8

self.assertEqual(expected, result)And a Makefile because python has an annoying, verbose test command

test:

python -m unittest discoverNow let’s check our work

git-intro git/main*

❯ make test

python -m unittest discover

.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

Ran 1 test in 0.000s

OK

git-intro git/main*

❯ python main.py 3

Hello world

Double 3.0 is 6.0Everything looks good, and we’re ready to commit.

❯ git status

On branch feat/double

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: main.py

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

Makefile

test_main.py

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

git-intro git/feat/double*

❯ git add .

git-intro git/feat/double*

❯ git commit -m "Add doubling feature"

[feat/double 6e0d74d] Add doubling feature

3 files changed, 27 insertions(+), 1 deletion(-)

create mode 100644 Makefile

create mode 100644 test_main.py

git-intro git/feat/double

❯ git status

On branch feat/double

nothing to commit, working tree clean

git add .the ”.” is saying add everything in the directory that im running this command from. Easier than specifying each file when we’re trying to commit more than a few.

Tip! If you had a

__pycache__folder when you rangit statusthis is a good opportunity to add a .gitignore, because those are not needed in our git history. Runecho __pycache__ > .gitignoreand re-run git status to see what’s changed. You’ll notice that the pycache folder is no longer there, but now the .gitignore file is. I would personally commit the .gitignore independently from the commit that implements your feature. The gitignore has nothing to do with the feature and the history should reflect that this was a change completely unrelated to it. Your commit history should tell anyone who’s looking at it how the codebase has evolved over time, and adding two unrelated changes into a single commit hides certain details that people may want to be able to find. There are lots of patterns for managing git and this is one of them, I won’t die on this hill and neither should you. What matters most is alignment in your team.

Looking at the log

git-intro git/feat/double

❯ git log

commit 6e0d74da9f9136ad1d959a4d48b3592a58b8cd2c (HEAD -> feat/double)

Date: Mon Mar 29 12:00:32 2021 -0400

Add doubling feature

commit 3c351805dd7fb4178507be8f61d54c0a592ffcd5

Date: Mon Mar 29 12:00:04 2021 -0400

Add gitignore

commit da8511f4b78f0b25b27e336a15538ac5c5ff481b (main)

Date: Mon Mar 29 09:47:38 2021 -0400

Hello world

commit 6b7a1fba279d8a1954223e086f9f04f511aef1e9

Date: Mon Mar 29 08:58:22 2021 -0400

First commitAnd now you’re ready to push! Once you push you can open a Pull Request and your code will likely be reviewed by a team member. Once the code looks good enough for main you will mostlikely be able to hit the “merge” button in the github UI. Finally you can switch back to your main branch on your machine, pull the changes and see that the main branch has been updated with the commits from your feature branch:

git-intro git/feat/double

❯ git checkout main

Switched to branch 'main'

git-intro git/main

❯ git status

On branch main

nothing to commit, working tree clean

git-intro git/main

❯ git pull

... I didn't actually push and PR

git-intro git/main

❯ git log

commit 6790485b595305c79592ff1cb08f91c9008fe0cf (HEAD -> main)

Merge: da8511f 6e0d74d

Date: Mon Mar 29 12:38:56 2021 -0400

Merge feat/double

commit 6e0d74da9f9136ad1d959a4d48b3592a58b8cd2c (feat/double)

Author: Shane Kennedy <shane.kennedy19@gmail.com>

Date: Mon Mar 29 12:00:32 2021 -0400

Add doubling feature

commit 3c351805dd7fb4178507be8f61d54c0a592ffcd5

Date: Mon Mar 29 12:00:04 2021 -0400

Add gitignore

commit da8511f4b78f0b25b27e336a15538ac5c5ff481b

Date: Mon Mar 29 09:47:38 2021 -0400

Hello world

commit 6b7a1fba279d8a1954223e086f9f04f511aef1e9

Date: Mon Mar 29 08:58:22 2021 -0400

First commitPull Request: when you push your feature branch to github you do it with the intention of getting it in to master/main, but when you work on a team you need to “ask” or request that your code be integrated in to the main branch and this is what a pull request is. With git clients like github you push your feature branch and open a pull request which informs your team that you’ve written code that you’d like to merge, and they will review it before that happens for quality assurance, knowledge sharing etc.

Notice the latest commit, it’s a merge commit and is the point at which your feature branch was merged into the master/main branch on github.

A way more intuitive way to look at this is by passing the git log --graph flag

git-intro git/main

❯ git log --graph

* commit 6790485b595305c79592ff1cb08f91c9008fe0cf (HEAD -> main)

|\ Merge: da8511f 6e0d74d

| | Date: Mon Mar 29 12:38:56 2021 -0400

| |

| | Merge feat/double

| |

| * commit 6e0d74da9f9136ad1d959a4d48b3592a58b8cd2c (feat/double)

| | Date: Mon Mar 29 12:00:32 2021 -0400

| |

| | Add doubling feature

| |

| * commit 3c351805dd7fb4178507be8f61d54c0a592ffcd5

|/ Date: Mon Mar 29 12:00:04 2021 -0400

|

| Add gitignore

|

* commit da8511f4b78f0b25b27e336a15538ac5c5ff481b

| Date: Mon Mar 29 09:47:38 2021 -0400

|

| Hello world

|

* commit 6b7a1fba279d8a1954223e086f9f04f511aef1e9

Date: Mon Mar 29 08:58:22 2021 -0400

First commitBonus: You just introduced a bug into main/master and it’s currently live for 100,000+ users!

This will happen, maybe not on your first day, first week, or first month. But it will happen. Probably multiple times. Here’s how to save the day.

So our git history looks like the git log —graph above, and you know it was your PR that is taking down production right now. There’s probably a lot to learn from this, and you should take the time to learn, but not right now. Right now it’s time to get things back to being stable. You need to revert this commit.

As always, changes that you want in master/main need to go through an approval/PR process. Start by createing a new branch and then let’s revert:

git-intro git/main

❯ git checkout -b revert/double

Switched to a new branch 'revert/double'

git-intro git/revert/double

❯ git st

On branch revert/double

nothing to commit, working tree clean

git-intro git/revert/double

❯ git log --graph

* commit 6790485b595305c79592ff1cb08f91c9008fe0cf (main)

|\ Merge: da8511f 6e0d74d

| | Date: Mon Mar 29 12:38:56 2021 -0400

| |

| | Merge feat/double

| |

| * commit 6e0d74da9f9136ad1d959a4d48b3592a58b8cd2c (feat/double)

| | Date: Mon Mar 29 12:00:32 2021 -0400

| |

| | Add doubling feature

| |

| * commit 3c351805dd7fb4178507be8f61d54c0a592ffcd5

|/ Date: Mon Mar 29 12:00:04 2021 -0400

|

| Add gitignore

|

* commit da8511f4b78f0b25b27e336a15538ac5c5ff481b

| Date: Mon Mar 29 09:47:38 2021 -0400

|

| Hello world

|

* commit 6b7a1fba279d8a1954223e086f9f04f511aef1e9

Date: Mon Mar 29 08:58:22 2021 -0400

First commit

git-intro git/revert/double

❯ git revert 6790485 --mainline 1

Removing test_main.py

Removing Makefile

Removing .gitignore

[revert/double 29c84c5] Revert "Merge feat/double"

4 files changed, 1 insertion(+), 28 deletions(-)

delete mode 100644 .gitignore

delete mode 100644 Makefile

delete mode 100644 test_main.py

git-intro git/revert/double

❯ git log --graph

* commit 29c84c58c88a53207ee2f616edf672f03a19dd88 (HEAD -> revert/double)

| Date: Mon Mar 29 12:47:19 2021 -0400

|

| Revert "Merge feat/double"

|

| This reverts commit 6790485b595305c79592ff1cb08f91c9008fe0cf, reversing

| changes made to da8511f4b78f0b25b27e336a15538ac5c5ff481b.

|

* commit 6790485b595305c79592ff1cb08f91c9008fe0cf (main)

|\ Merge: da8511f 6e0d74d

| | Date: Mon Mar 29 12:38:56 2021 -0400

| |

| | Merge feat/double

| |

| * commit 6e0d74da9f9136ad1d959a4d48b3592a58b8cd2c (feat/double)

| | Date: Mon Mar 29 12:00:32 2021 -0400

| |

| | Add doubling feature

| |

| * commit 3c351805dd7fb4178507be8f61d54c0a592ffcd5

|/ Date: Mon Mar 29 12:00:04 2021 -0400

|

| Add gitignore

|

* commit da8511f4b78f0b25b27e336a15538ac5c5ff481b

| Date: Mon Mar 29 09:47:38 2021 -0400

|

| Hello world

|

* commit 6b7a1fba279d8a1954223e086f9f04f511aef1e9

Date: Mon Mar 29 08:58:22 2021 -0400

First commit

git revert <commit_id> --mainline 1you need to specify a mainline argument when reverting a merge commit. Here is the best explanation of why.

Notice you have a “revert” commit, if you were to run git show (without any argument this shows the latest commit, very useful to know) you would see the undoing of all changes that we made in feat/double, not just the last commit or the first one, but both of them.

Then push this branch, open the PR and send an @here in your slack’s dev channel to let people know you have the fix and it needs some eyes.

Concluding

And that’s the basics of git and what you need to get going. There are lots of editor integrations that can help simplify this workflow but it is absolutely worth knowing what’s actually going on under the hood; knowing this will provide a solid understanding of git, help you master the more advanced commands that weren’t covered in this post, help you reason about the more advanced features that you see in whatever editor integration you use, and just anecdotally I can tell you having a strong understanding of git has helped me troubleshoot and resolve multiple issue in my career. Last but not least, this is something you’re going to use everyday for the rest of your code-writting life, you don’t want it being a pain point in your workflow.